Hariharan Subrahmanian brings into the attention of the world through his augmented photographs the truths and his concerns about contemporary India with all its glaring issues of migrant laborers, gender inequality, environmental degradation, social injustice, and above all, the political apathy. Embedded in these images are the inner turmoil the artist experienced while deciphering the ‘unintelligible truths’ that occurred to him while under the lockdown of the COVID season.

Artist’s Statement:

While a painter, sculptor, or writer could work from the solitude of his/her studio or study, the photographer was in a quandary. (S)He was unable to go out into the vast world and work. It was a forced “Rear Window” situation for him/her. Scores of photography fora in the social media started to run a “Lockdown Diary” series and soon their pages were filled with images shot of people, pets, garden foliage and everyday objects found in homes. It was a bit disheartening to see images that displayed a certain kind of universalised banality not only being taken and but also posted with such unfailing regularity.

On the social front, things were in dismal ferment. A month into the lockdown, people were starting to feel the pinch.

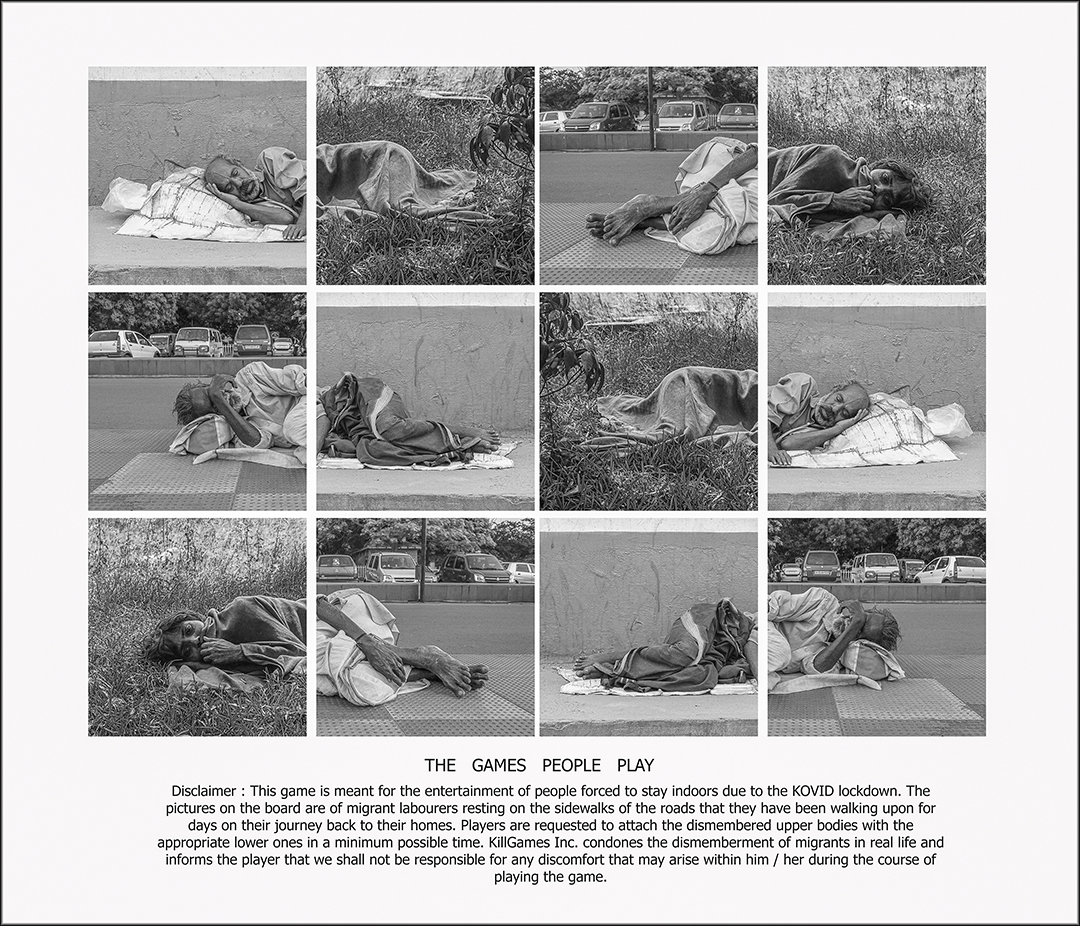

Millions of migrant labourers, caught in an existential warp thousands of miles away from their ancestral land and left with no option, decided to walk back home. Penniless and hungry, they trudged along under a harsh summer sun. The “Great Indian Migrant March” was doomed to be disastrous.

A majority of newspapers and channels, fearful of a vengeful State, chose to ignore them. It was the social media that broke the events of the unfolding tragedy. With people starting to realise that things were amiss, the mainstream media had no option other than joining in with their coverage.

By then the lack of true empathy with the migrant worker’s situation had made itself glaringly evident.

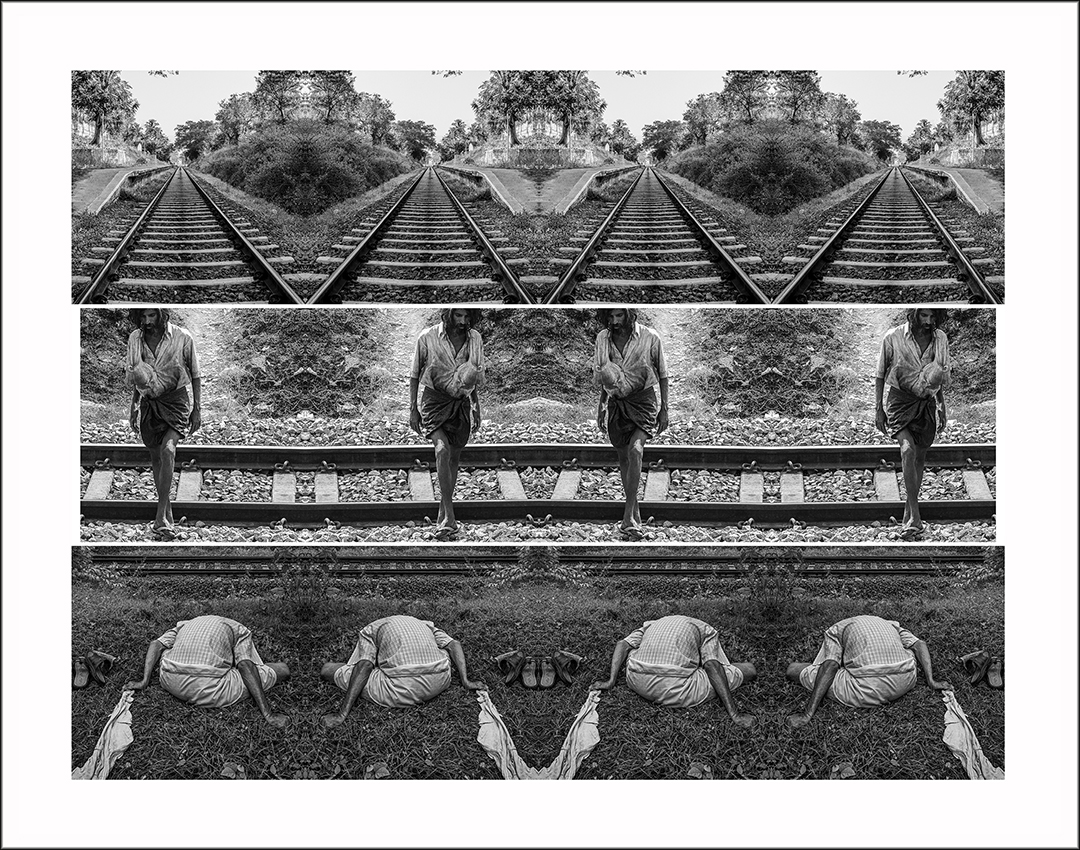

The highways and railroads all over India had hordes of the poor and dispossessed trudging back in exhaustion. These pathways soon turned to be Grand Highways that led to Death. People started to die, just walking…

The height of tragedy occurred near Aurangabad where a group of exhausted labourers walking their way home with barely a meal in their bellies, fell asleep by night on the tracks. In the darkness, they were run over by a goods train.

Remarks to the effect that people would indeed be killed if they happened to sleep on tracks that were meant for trains to run were made by ministers and netas. It was all just a game for them after all.

They were in hot pursuit of the Ball of Power to score their goals with while the ‘bhadralok’, secure in their comfortable locked down homes, remained spectators, and added fervour to the frenzy with their mostly callous comments on social media.

The situation was a desperate one.

As a concerned artist, I was helpless as public transport had ceased operations a month earlier, and travelling to document the times was impossible. State borders were closed for private vehicles.

I had started a documentation project on migrant workers from Tamil Nadu while working a few years ago at Walayar, a border town between Coimbatore and Palakkad, during the course of my career stint with the Railways.

And then it struck!

It is the same spirit of the migrant worker in his eternal pursuit for a minimal modicum of prosperity, despite being always treated as dispensable and being killed now, that was within the Tamilians I encountered daily a decade ago in Walayar.

Walayar, in 2010, and Aurangabad now, I realised, were identical for the poor of India with their all-too-human aspiration for a slightly better life for themselves and their children.

I had found my creative solution.

In a flash of insight, I realised that I could create works that would comment on the burning contemporary reality that was haunting me night and day with imagery I had shot earlier. Because both stem from precisely the same issues, the same experiential universe – the struggle between the human aspiration for survival against the almost insurmountable great wall of socio-economic inequity and suffering.

My eyes opened to the slender but unbreakable nylon strand of oppression that connected the forlorn migrants of Walayar with the hapless death row inmates of the highways in Northern India. They were one and they shared the same ignominy of defeat.

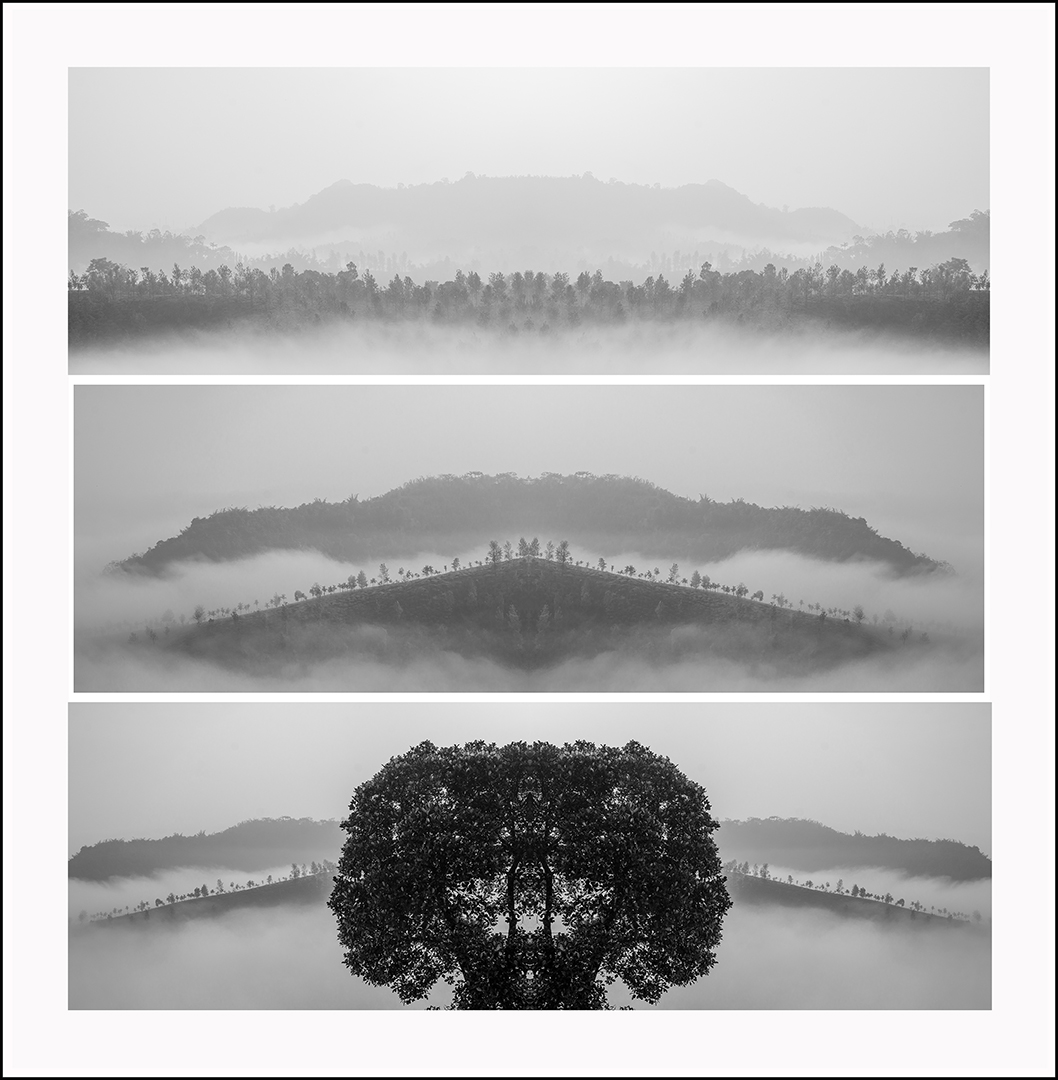

The unofficial censorship or rather the self-restraint practiced by a compliant media ensured that the citizenry remained blissfully unaware of the subversion of environmental laws happening meanwhile in the shadow of the lockdown. People who were growingly aware of the decay that had started to set in were unable to assemble and register their protest due to the social distancing norm that had to be followed due to the pandemic.

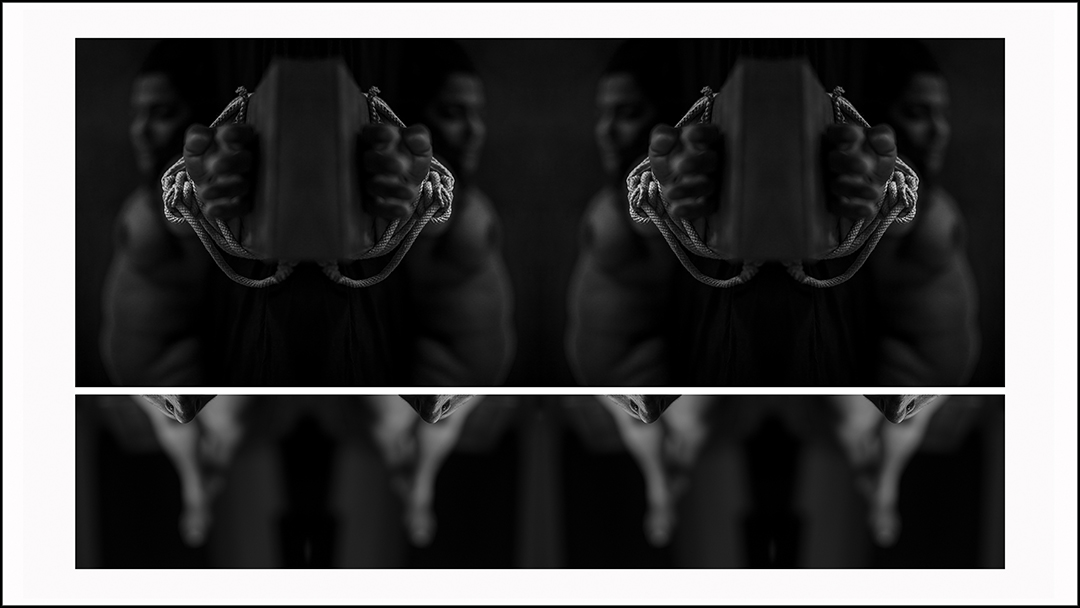

A whole lot of extant protective laws, like garments that cover a body, had been stripped off and the body laid bare to the lust ridden vulgar gaze of rapacious molesters. They now only had to close in for the kill.

New laws that would protect the killers after their deeds are on the anvil too. Over a hundred changes have been mooted to happen six of India’s most stringent environmental laws that had lent sanity to the nation’s fight to protect her natural heritage and wealth. It was too shocking, and little attention was being paid to it. The fact that nearly half-a-dozen laws concerned with the environment, forests, wildlife, water and air pollution could be compromised would make one realise the severity.

Our natural landscapes are receding fast and it seems that they will disappear altogether very soon.

The four pillars supporting the edifice of a badly hit nation have been compromised with grave and unjustified interference. Yet, we are expected to believe that they are exceptionally adequate to hold us up. The intricate carvings on the exterior of the four pillars bedazzle us and like the sirens’ melodies, they lead us like bewitched sailors under a spell.

On the surface, an intelligible lie, marinated in the sauce of rhetoric is showcased for us to see, wonder, and applaud. Beneath, swept under a red carpet, as ugly as only it can be, lies the unintelligible truth.

India’s Great Sale is on and everything is up for grabs. Her labourers…Her forests with the natural mineral wealth they hold…Her women…

All of these and others have been brought under the hammer and the Big Daddy of all auctions has started in earnest.

It was Ansel Adams who had defined the photograph as not merely an image produced by the camera.

“You don’t make a photograph just with a camera. You bring to the act of photography all the pictures you have seen, the books you have read, the music you have listened to, the people you have loved.”

The dismal stories that the social media and later, the mainstream media brought to me, at a time of darkness perhaps added to this repository of feeling.

It’s a time of darkness that I find myself with my countrymen in…And perhaps, taking after Bertolt Brecht’s famous lines, the songs we sing will definitely be of that darkness as well. The photographs we make too would have a histogram that leans a bit to the left.

Leave a Reply