The tragic epic Silappathikaram continues to influence popular culture through contemporary cinema, theatre and music. Most of these narratives continue to propagate two moral characteristics from the epic – chastity and virtue, the two main ones with which society in South India is framed. This method of recreating the story conceals the outstanding social, economic, and political milieu described in the epic.

It was precisely this concealment and the attempt by the photographer Abul Kalam Azad to enlighten the viewer about the descriptive narration of Ilango Adigal in the epic that formed the main part of writer and filmmaker Tulsi Swarna Lakshmi’s discourse which marked the 14th edition of Alchemy, an initiative of Photo Muse, India’s first public museum dedicated to the art, history and science of Photography, on August 28, 2021.

“Every photograph has encoded and decoded meaning that is universal and cultural. In fact, every part of the photographic image carries some information that contributes to its total statement. A conceptual and contextual reading of a photograph sees and consciously responds to the ‘secretly coded’ signs and symbols. However, as photographs are culturally situated, they convey different meaning to different viewers, based on personal life experiences, knowledge, political perspectives, and socio-cultural conditioning. Furthermore, they open up the possibilities for multiple interpretations based on where, when, and how it is published/exhibited, and who were its intended audience/end users. The same photograph published in a magazine, when exhibited in a museum connotes a totally different message. Another way of cropping, or, even a change of color mode to grayscale, could distort the aesthetics and the intended/perceived meaning.”

“That way, the statement an image makes is not just what is present within the frame but also what is absent – what was excluded from the frame. The original intent, the socio-cultural and economic background, and the political inclination of the artist, the context or event during which the photograph was captured, the mood or emotion it communicates, the methodologies in which the artwork was exhibited / displayed / installed, and the intended/resultant use of the creations – all these contributes to the reading of the photograph. The aim is then to decipher and decode its meaning that is simultaneously personal, cultural, political, economic, dramatic, sociological, every day and historic.”

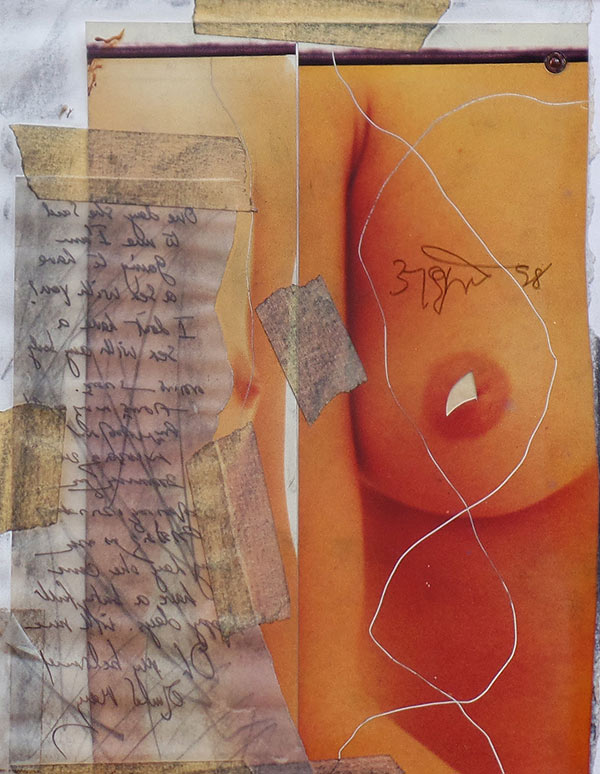

© Gauri-Gill

“Constructing a radial wheel of narratives around a photograph will facilitate a systematic reading of a photograph” – elaborated Tulsi Swarnalekshmi.

Photography is the most modern and democratic visual art medium that has gained popularity like music and poetry. With digital technology, it has become an easy one-click application, making anybody and everybody a photographer, Ms. Swarna Lakshmi noted, adding that every photograph has value, and captures a slice of history that contains several layers of information and memories. Even the casual images and personal records offer meaningful insights. However, the work of a thoughtful photographer has greater importance as a work of art and epigraphical document. It can become the symbol of culture and lifestyle, a prised visual treasure to be protected and promoted.

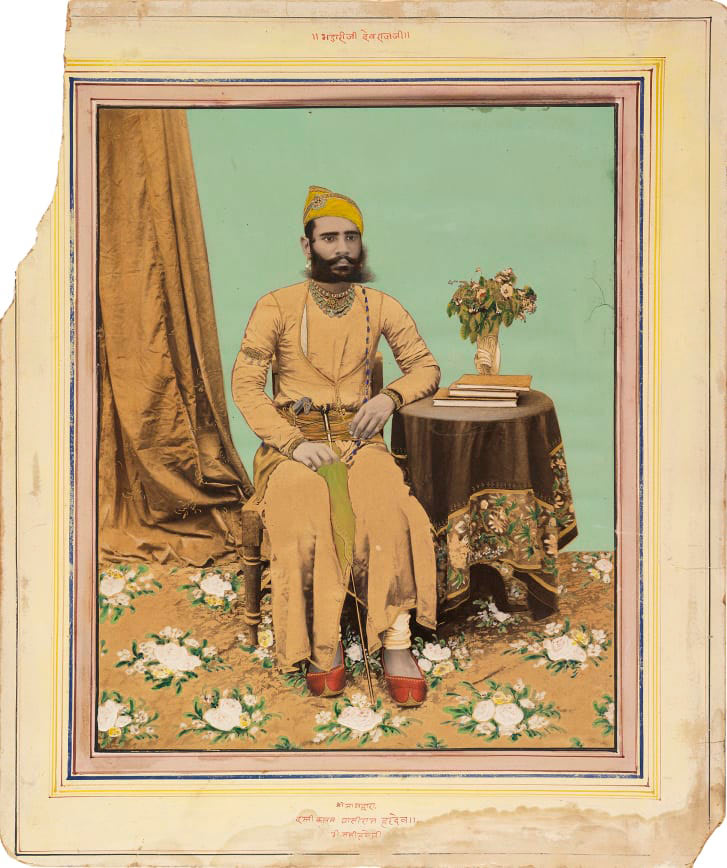

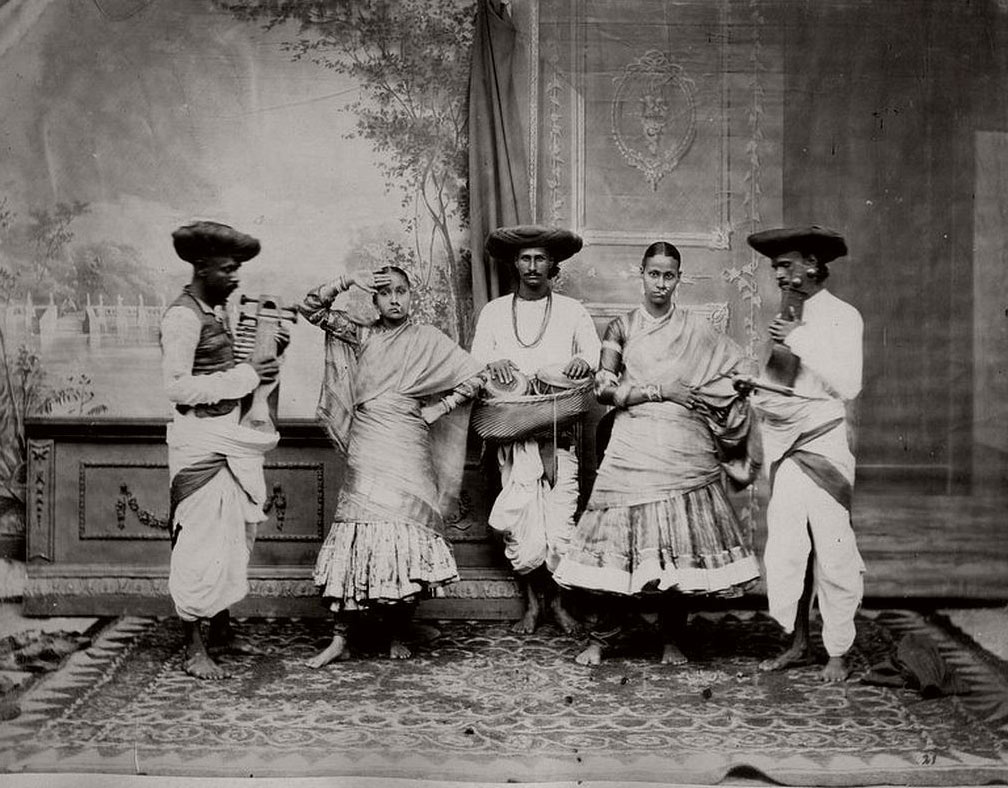

Painted photograph, 19th century India

She gave a brief introduction on photography right from its invention in 1839 to the invention of the Kodak camera in 1888, the Russian Constructivism, Dada and Surrealism between 1913 and 1940, parallel activism that included Straight Photography that boomed in 1916, then Modernist Photography in 1931, the Abstract Photography in 1945, and to the new landscape and postmodernism that evolved in 1975. She moved to the Indian scenario and explained in brief how photography and photographic societies evolved during the colonial period in the 1840s, and talked about the Indian avant-garde from the 1980s till 2000, then about Indian Post-modernism in 2000, and the Memory projects in the mid-2000.

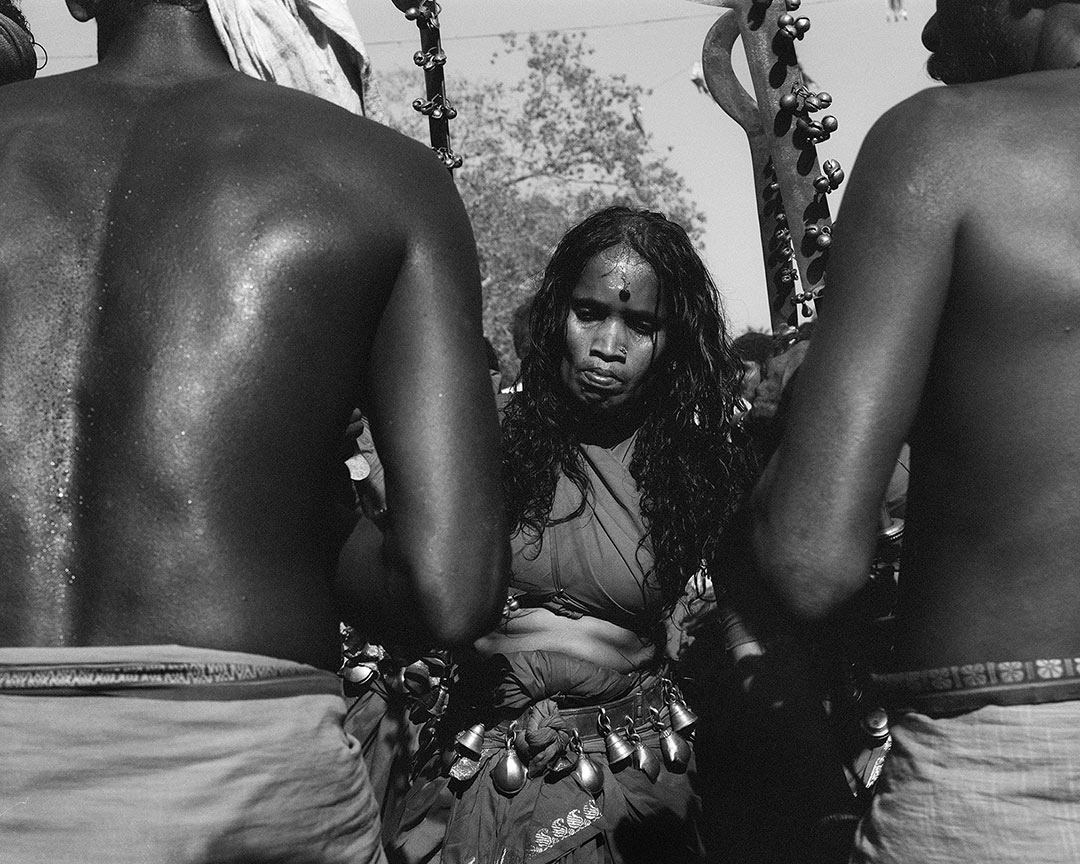

© Abul Kalam Azad

Ms. Swarna Lakshmi, the Founding Managing Trustee of Ekalokam Trust for Photography and the Executive Editor of Photo Mail, opined that Azad created a parallel visual narrative of the tragedy. Ilango has given an evocative picture of the land, landscape, people, lifestyle, flora and fauna, rulers, culture, caste, festivals, rituals, long journeys of traders, local economy, family, love-life, fish, rivers, seas, various seasons, flavours and sounds, ancient dance forms, music, songs, costume, etc. of that age.

Azad’s large body of work named ‘Story of Love, Desire and Agony’ is a re-examination of the classical tragic epic in contemporary circumstances. He targets his camera on the diverse aspects of the still persevering practices and rituals of the Mother Goddess cult, the distinct landscape of South India, the remains of the cross-border cultural relations, and the epic’s impact on the social genesis in the South, observed Ms. Swarna Lakshmi, who has more than a decade of experience working with leading national and international NGOs in India, Africa, and South America.

Sangam Literature:

Madurai, the capital of the Pandya dynasty, was once the hub of poets and scholars from the three ruling dynasties – the Pandyas, the Cholas, and the Cheras of ancient ‘Tamilakam’. The men of letter used the might of art and literature to bring the people of their territory together. They successfully used the language of Tamil to unify the eternally quarrelling trio regions. The literature of this period is popularly known as the Sangam Period which gave birth to around 2,381 poems composed by 473 poets and poetesses who came from different backgrounds and walks of life. Though the poems look melodramatic and farfetched, they do provide a lot of valuable insight into the social, political, economic, and cultural aspects of the period.

Sangam poetry is classified into two types – ‘Akam’ or inside or lust and ‘Puram’ or outside or valour. While the poems in the ‘Akam’ group narrate the love life, family, etc, the poems in the ‘Puram’ group chronicle personal integrity, culture, society, war, economy, trade, ruler, etc. Each poem not only says about their particular region but also about the people who lived there and their feelings, animals, plants, trees, flowers, etc.

Silappadhikaram, the epic poem:

Silappathikaram or the story of the anklet, the epic poem composed by Ilango Adigal during this period, probably in the 5th or 6th century CE, stands out. The prince-turned Jain monk, Ilango, describes a prominent folktale associated with the native custom of worshipping Mother Goddess. This classical tragedy is set in the backdrop of all three territories and includes the coastal and inland life of ancient Tamilakam.

With all the inherent features of Sangam poetry, the epic of 5,730 lines has three ‘kandams’ or sections which are further subdivided into ‘kathas’ or cantos. The three sections are named after the capitals of the three dynasties. The first section ‘Puharkkandam’ is all about the events in the Chola capital Puhar also known as Kaveripumpattanam, where the river Kaveri meets the Bay of Bengal. Here Kannagi and Kovalan start their married life, and Kovalan leaves his wife for the courtesan, Madhavi. This section falls under Akam or inside genre.

The second section ‘Maduraikkandam’ is set in Madurai, the capital of the Pandyas. Here the couple is trying to rebuild their lives after leaving Puhar and Kovalan is executed after being falsely framed for stealing the queen’s anklet. In an act of revenge, Kannagi burns the whole city. Gods and goddesses meet Kannagi and she herself is revealed as a goddess at the end of this section that falls under Puranam or mythic genre.

The last section ‘Vanchikkandam’ is based in the capital of the Cheras, Vanci, where Kannagi takes off to heaven in the chariot of Indra. It also narrates the story of the Chera king, queen, and the army building a temple for Kannagi as Goddess Pattini. Falling under the genre of Puram or valor, this section also narrates the journey of the Cheras to the Himalayas and battles along the way.

At a time when it was a custom to make the ruler a hero in the poetry, praising and exaggerating his virtues, Ilango used Kannagi, an embodiment of the Mother Goddess, as the central character of his work. Contrary to the popular norm of the age of venerating divinity in the beginning, the work glorifies the river Kaveri, the Sun, the Moon, and the city of Puhar. The Sangam society followed the cult of mother goddess and nature worship and it got reflected in Silappathikaram.

Metabolism of culture:

“Culture – that continuously changing complex whole, is usually acquired by a group of people at a particular time, either through natural progression or through external force. Thereupon, it is often used politically as a tool by the elites to manipulate and incarcerate societies within ‘certain’ manufactured symbolisms and moral contexts. It becomes a chain to which one is intricately tied to – its origins forgotten and original purpose thwarted. Metabolism of Culture through the photographs of Abul Kalam Azad seeks to understand its origins and multi-fold assimilations by decoding the hidden meanings and layers of thought behind these seemingly simple and straightforward monochrome images” – says Tulsi.

© Abul Kalam Azad

Born in a progressive Tamil Muslim family, Azad began traveling at a very young age. His adventure took him to different parts of the country as well as abroad for a decade. Once he returned from the western world, he started examining the origins of Gods. Before coming back to the motherland he did a series, ‘Goddesses’, for which he collected sex call cards from Soho in London, and scanned them into enlarged images, and did hand sequence work on the silver gelatin prints.

In 1999, photographer Abul Kalam Azad set out from Mattancherry in search of his family roots. He was always intrigued by how his family in Mattancherry got the name “Pattanam”. In the pursuit of his roots, he got introduced to Silappadhikaram composed by Ilango Adigal.

The cultural variation between the nations he had visited and the undying mission to probe into the roots of this multi-faceted world stimulated him to begin his photo series project. He wanted to explore what the men explained by Ilango during the Sangam period looked now and the outcome is an incredible series of images, constituting statues and places of that era that still stand and portraits of men and women from different backgrounds, castes, communities, and classes.

Chasing the ‘Story of Love, Desire and Agony’:

He resumed his cultural quest for the conventional Mother image by shooting the Mother Goddess cult worship at Kodungallur Bhagavathy Temple. The extensive five-part photo series, which he named as ‘Story of Love, Desire and Agony’, captured at Kodungallur Bhagavathy temple, deals with identity, gender, and territory. The native folklore myths link the presiding deity and the pre-Vedic Hindu ritual offerings with the legendary Kannagi.

Silappathikaram deals with three main factors – love, desire, and agony. It is the tale of Kovalan, a merchant in the port of Pukar, and the conflict of love and desire he goes through between his wife Kannagi and his lover Madhavi, accompanied by the agony that follows them. Thus, Azad named the first part of his series as Story of Love, Desire and Agony!

© Abul Kalam Azad

Through ‘Black Mother’, the first in the series shot in 1999-2000, Azad composed the rituals of the divine feminine or the mother goddess cult among the women of Kodungallur. His Black Mother was primarily attributing to Kannagi in Silappadhikaram.

During the Meena Bharani festival at this Bhagavathy temple, the male and female oracles and villagers consider themselves to be controlled by the Mother Goddess and ceremoniously make an offering to the presiding deity. The surroundings vibrate with the clang of their heavy anklets and the scent of turmeric, pepper, and blood. Oblivious about the gathering, the oracles, with scythes in their hands and anger gleaming on faces, sing and dance in various levels of stupor around the temple. Regionally known as “Kavu Theendal”, this is nothing but an extension of the Sangam period Mother Goddess cult worship.

© Abul Kalam Azad

The second part of the series was shot at ‘Contemporary Heroines’, shot in 2015 at Mathilakam, 10 kilometers from Kodungallur. Mathilakam was earlier known as Trikkana Mathilakam, the village where Ilango Adigal is supposed to have been living while composing his masterpiece. Here Azad tries to unveil the shades of socially accepted womanhood, an idea shaped by the cultural norms of the Sangam period.

He continued his Black Mother series with portraits of present-day women of Mathilakam. The women are those whom we see every day, but in each frame, they’re heroines of their own untold saga. They look not only beautiful and striking but also intense and sometimes sad and gloomy. They strike a balance between the violent Black Mother and the calm Black Mother, showing a kind of personal metamorphosis of the artist in his thoughts over the years.

© Abul Kalam Azad

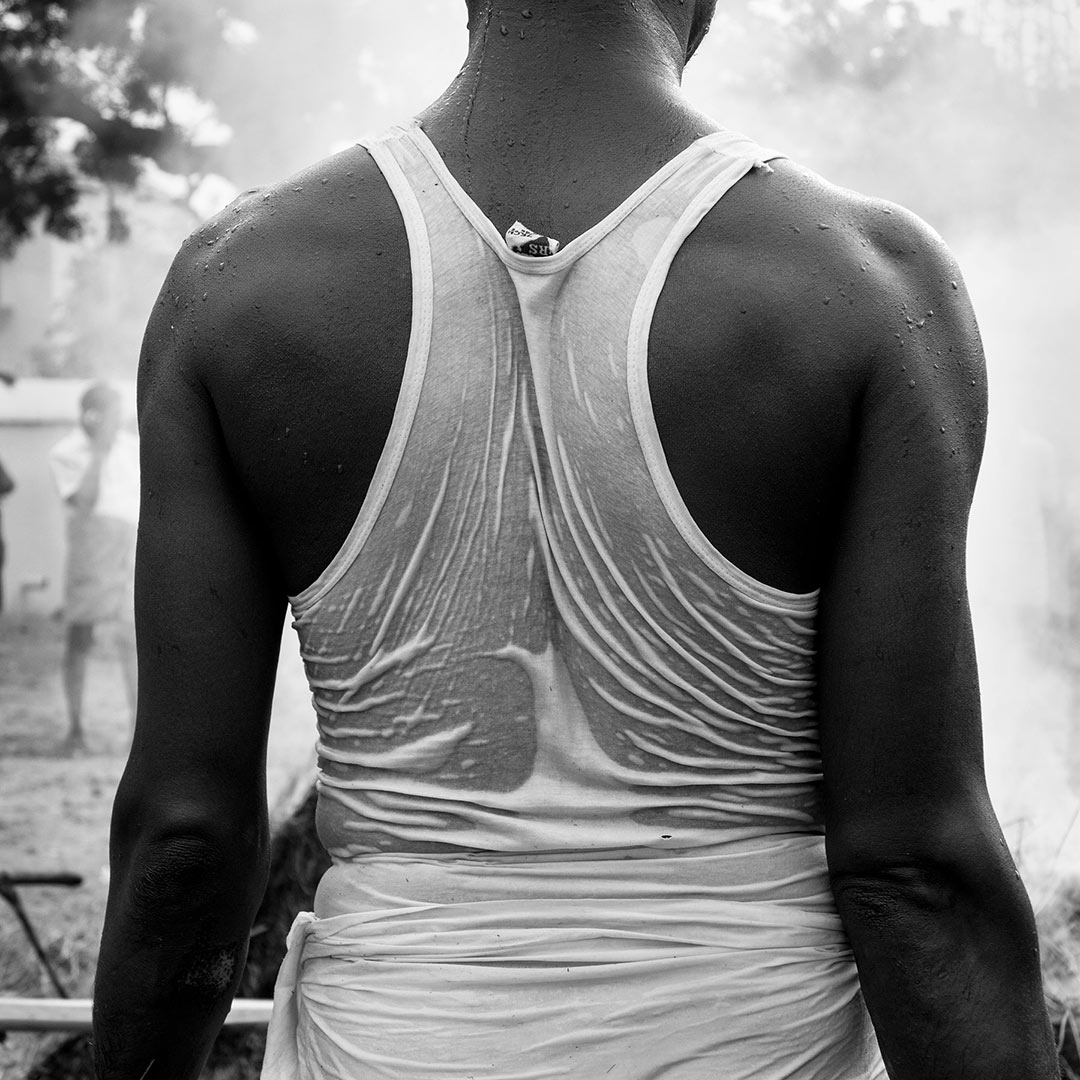

In his third part of the five-part series, titled Men of Pukar, Azad ventures to re-look and rediscover Ilango’s Pukar and its men in the present-day scenario. He captured the images in presentday Poompuhar, the ancient port town at the estuary of the river Kaveri in Nagapattinam district. Although the present-time men of the port town are no longer the aggressive warriors and ardent traders narrated in the epic, their lifestyle is still influenced and built by the same surrounding, one that is connected with the river Kaveri and the sea.

At present, Azad is in Wayanad doing the fourth and the fifth parts of the series.

Interpretation of Azad’s work:

“On the whole, Abul Kalam Azad’s photographs deal with the issues of identity, territory and gender. He attempts to unpack and unravel multitudes of identities and shared lineages that are at present commonly considered monolithic and static. His central themes have remained the same throughout his four decades of photographic practice, yet they are so varied in content, form and expression. His versatile style zigzags between complex and experimental to simple and straightforward.

Defying the now popular high definition graphical photography, in Story of Love, Desire and Agony, Abul adopts a minimalistic style. The series encompasses and builds upon his personal and political reflections over the past two decades. In a way, Silappathikaram, believed to have been composed/compiled two thousand years ago becomes a tool for him to ask some pertinent questions around issues that our society faces now. Taking a deeper look at this epic tragedy, Abul juxtaposes the still lingering bits and pieces of the Sangam society’s culture and tradition with the shifting social reality. His parallax vision of the epic and contemporary society is not exotic; the aesthetics is not that of the forlorn foreign perspective; and, he is more than a mere spectator.”

© Abul Kalam Azad

Ms. Swarna Lakshmi elaborated the works of Azad with some of his images from the series. ‘Palmyra’, depicts the caste system in India. In South India, tapping toddy from palmyra and coconut palm trees was done by indigenous people who were later named Chanars. Palmyra tree was considered miraculous that could grow up to 100 feet and climbing it was a specialized job done only by the men belonging to this particular community.

‘Parathavar’, shows the etymology of the Naval force. The life of fishermen has a kind of rhythm and timing that matches Mother Nature. Their entire day depends on the weather, water current, movement, and life cycle of fish.

‘Cauvery’, depicts the river valley civilization. The Kaveri, the lifeline of South India, is epitomized as a woman, rather than as a mere Goddess. So many customs, along her course through the four states, have been practiced since ancient times. The most important being the one performed at the mouth where the river joins the mighty ocean, the culmination of a voyage often compared with the passage of human life.

Azad has worked for nearly two decades as a photojournalist for various newspapers and magazines in India and abroad. He held several exhibitions of his works and is a recipient of the senior fellowship from the Ministry of Culture. He started an art collective ‘Mayalokam’ in Kochi and organized, along with other artists, art initiatives like ‘Encounter’, a contemporary art festival, which Tulsi describes as a kind of forerunner to the Biennale.

While photos in color give an absolute concept about the subject to the viewer, the monochrome images intrigue the audience, forcing them to decipher the subject on their own. And this is what Azad wants from his audience. Throughout the photo series, Azad maintains a greyscale for his images and leaves the viewers to interpret his frames in their own way. After all, as John Berger notes in his ‘Uses of Photography’ About Looking (London: Bloomsbury, 2009) 52-67 [An essay for Susan Sontag, in response to On Photography], “It is because the photographs carry no certain meaning in themselves, because they are like images in the memory of a total stranger, that they lend themselves to any use.”

Author

Ms. Chaitra Arjunpuri

Leave a Reply