A Wet Plate Collaboration by Shane Balkowitsch

July 17th, 2021, University of Mary, Bismarck, North Dakota

Ideas come from everywhere. Occasionally we self-generate. More often they are thrust upon us. For the past five years, I have organized an annual photographic Tableaux Vivant based on classic paintings. I have included anywhere from 15, or in the instance of my 2021 construction, No Vaccine for Death, ninety (90) collaborators. Photographic history is certainly replete with expansive portraits. Utilizing a digital camera, group portraits can be captured quickly and at a moment’s notice. My portraiture, however, differs vastly from the work of contemporary photographers as I turn the clock back with Frederick Scott Archer’s 1851 medium of wet plate collodion. Presently, less than 1000 photographers practice this archaic form of photography worldwide. I am very proud to be one of them.

To make a wet plate, liquid collodion is poured over a piece of polished black glass, sensitized in a bath of silver nitrate, exposed in the camera and then developed immediately (under safelight conditions) …usually within minutes, as to not allow the collodion to dry on the plate and lose the image. For location work, I have built a portable darkroom that is easily transported. All development must be done instantly and on-site. For the techies, I use an Alessandro Gibellini 8×10-inch bellows studio camera mounted with a Carl Zeiss Tessar 300mm f4.5 lens and a manual lens cap. No Vaccine for Death was shot outside under the open haze of a Bismarck, ND sky (artfully and unfortunately provided by the California wildfires) with a one-second exposure at f11.

No Vaccine for Death is the 5th large production that my friend, collaborator, project director and St. Mary’s College (of Bismarck) film professor Marek Dojs and I have worked on together. Each time we start a new project it seems we get more ambitious and attempt to push the envelope of what is, or seems to be, possible. Two years ago, our project was going to be something completely different. We were going to re-interpret a painting of saints descending from, and people ascending to, heaven. The image personified the conflict between the ideas of good and evil.

When COVID hit, we knew we had to confront the pandemic.

With the onset of COVID, life, as we well know it, changed in a heartbeat. Marek said “In regards to the theme – one thing that I’ve been thinking a lot about is how afraid of death our society has become. The idea that we will live forever, and that pain and suffering should be avoided at all costs, has created a lot of problems in our time. The pandemic brings the possibility of death closer to us, but death is the real pandemic – and there will be no vaccine for that – we will all die. “No Vaccine for Death” might be an interesting title…”

At that point, No Vaccine for Death was born. In a meeting several days later, Marek and I discussed The Triumph of Death, Pieter Bruegel’s 1562 masterpiece which hangs in Madrid’s Museo del Prado. Inspired by the unstoppable onslaught of Europe’s Black Plague which killed over 25 million people (nearly a third of Europe at the time, and which lingered on for hundreds of years longer), our wet plate shoot could not have come at a more poignant time in modern history. The world had just started to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. Marek and I thought that if we could immortalize this scene through our visual vocabulary, we could put COVID behind us. Marek, cognizant of our inevitable death, felt that if people focused so much time and energy on things that are not important, we would lose track of our time here on Earth. He wanted to stress the fact that there is no vaccine for mortality. In so doing, we attempted to pay homage to Bruegel’s original image.

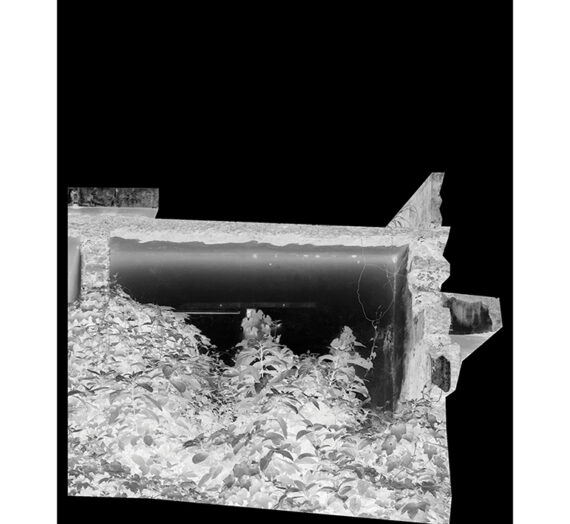

With the concept firmly in hand, our efforts turned towards the logistics of production. Needing an open and accessible location, my first call was to Monsignor Shea, the President of the University of Mary, here in my hometown of Bismarck, North Dakota. The sacred Marian Grotto which formed the basis for the scene is on the college grounds. The stone arch of the grotto was a close match to the stonework in our inspirational painting from 459 years ago. I then enlisted the aid of Michael Stevenson and Michele Renner Oster, directors of the local (Shakespearean) theatre companies for the creation of costumes. Forty back-up and support personnel, including make-up artists, hair stylists, carpenters, dressers and armorers were pressed into action. Dozens of skeleton costumes were purchased, altered and fitted to for the various volunteers. As a matter of fact, once the call for actors went out on social media, over 100 respondents ranging from local university students to photographers from San Diego, St. Louis, and Cleveland, Ohio, asked to be part of, then joined, the collaboration.

Finally, the morning of July 21st arrived. I had barely slept. At 6:00 am I was on site with a flatbed pick-up truck arranging camera angles and laying out the relative positions of each of the participants. By 8:00 am the temperature had hit 80 degrees (on its way to 100 a couple of hours later). The intrepid actors were in full-length Renaissance costumes and ready to be placed. I estimated it would take at least eight collodion plates to get the perfect shot. Each plate would take a minimum of 30 minutes to expose, develop and evaluate, let alone allowing the actors time to stretch, move around, grab a bottle of water, and then reset. As it is often said, a wet plate is not taken, it is given to you. I was prepared to work until I had a satisfactory image. Fortunately, my crew was likewise committed.

I mounted the truck, double checked the exposure and left to coat the first plate with collodion. Marek, bull horn in hand, directed the actors to their positions. The first plate was over-exposed. Nailing down a precise exposure on a first attempt using natural light is always a challenge. Reset, I took another plate which I judged as adequate. It’s now an hour later and the sun has really begun to take its toll. As a third plate was exposed, we were beginning to see our vision for the shot unfold. Everyone gathered around to see the results once the plate was washed. A cheer went up with the general agreement we were close. We took a short break and went for our fourth and final plate of the day. All the elements we were trying to incorporate and capture became visible. We had our one plate, the plate that would represent our 18 months of planning. The final plate is being donated to the State Historical Society of North Dakota with a list of all of the collaborators that were involved. We had something to show for our moment in the sun. A pure silver-on-glass image when properly curated will exist for hundreds if not thousands of years. One second of our lives has been immortalized as a reminder to others of our time together.

Pizza served. Champagne uncorked. Camaraderie exchanged. Congratulations were shared by all. We were asked by the local media if this is the largest “live” wet plate collaboration of all time. To that, we had no answer or concern. We just wanted to come together for no other reason than to create as a group. The history of our time together will be left up to others to determine.

I want to thank every person that contributed to this fabulous adventure. I am so blessed to be on this creative path with all of you.

Author

By Shane Balkowitsch as told to Herbert Ascherman

Leave a Reply