The memory of bygone days is the key to enter the world of photography. These memories bring up emotions that are flashy, radical, complex and innocent. The feelings of sadness, bitterness and detachment are also attached with some of these photographic memories. ‘Images of Encounter’, a virtual exhibition of photographs, is a treasure trove of memories from across the globe. Here, one can feel the photographs mesmerizing the senses. While experiencing the exhibition one can imagine the neurons firing the feel-good dopamine and the serene serotonin flushing and expanding the consciousness. With this exhibition, the Ekalokam Trust for Photography has curated and hosted a digital space that is so evolving. The parents and foster parents of this exhibition have experimented with a wide universe of ideas and galaxies of symbols, transferring arcane and poetic associations to the viewers.

While exploring the microcosm of the word ‘Encounter’, it can be understood as having a raw subjectivity attached to it. The word is not fixing any single meaning to the exhibition, instead one can gather several thought connections, refined memories and insights. Whatever may be the case, the Images of Encounter has written a new chapter in the annals of Indian photography exhibitions. The curators have termed the show as ‘Imagining the realm of the real’. It is a questioning of life, from a more detached mode. Is the show of life we are all part of, merely a chance, a coincidence, or a dream? Or is it the realm of the real? What controls the symphony of life which we see in colors and the shades of grey? With the whole world stuck indoors and brooding over the existential crisis brought up by the coronavirus, digital spaces are opening up new doors for creative expressions. ‘Images of Encounter’ is such a new door.

The feedback and observations regarding an exhibition have immense importance. Every human being we encounter, including ourselves, carries the accumulated consciousness of a long chain of ancestors. This collective memory is the architect behind the umpteen civilizations that thrived and perished on the earth’s surface.

It is often said that history repeats itself. Anyone going through these photographs can slowly fill the jigsaw-puzzle, the riddle of what we are. We are our elders, an extension of a big fall, recycled by the soil and dust.

The exhibition has quite a few known names, Martin Parr, Robert Nickelsberg, David Bate, Sunil Gupta, Nick Oza, Ram Rahman, Abul Kalam Azad, Parthiv Shah, Alex Fernandes, Dinesh Khanna, PunalurRajan and many more. Shibu Arakkal, Yannick Cormier, Swarat Ghosh, Taha Ahmed are emerging photographers who are making their own distinct mark. There are also quite a few young names, Lina Issa, Arun Inham, Naveen Gowtham, RamithKunhimangalam, some of whom are exhibiting for the first time. Mukhul Roy, a veteran photographer who has a made a significant contribution especially in India, is not a known figure, but her large oeuvre demands special mention. As a collective, there is much to see and take – with different genres of photography at play. With this sort of open “Encounters”, a new horizon unveils – a lot has to be read between the lines. Each exhibit is stand-alone, yet often it circles back, becoming more emphasized in another photographer’s works as if an invisible thread connects the otherwise diverse works.

Legendary British photographer Martin Parr is professionally a documentary photographer. In his ‘Death by Selfie’, he talks about taking selfies. The world is presently living amid a selfie culture, visually documenting itself like never before. In this narcissistic lifestyle, accidental deaths have become a companion for several selfie lovers. In Death by Selfie, today’s everyday scene becomes sociological and psychological study materials to be explored. Have selfies killed photography, or has it empowered photographers to develop distinct styles and conceptual expressions? Martin Parr once again reiterates that it is rather the latter and a whole new prospect has opened up for photographers to further delve into this fascinating medium.

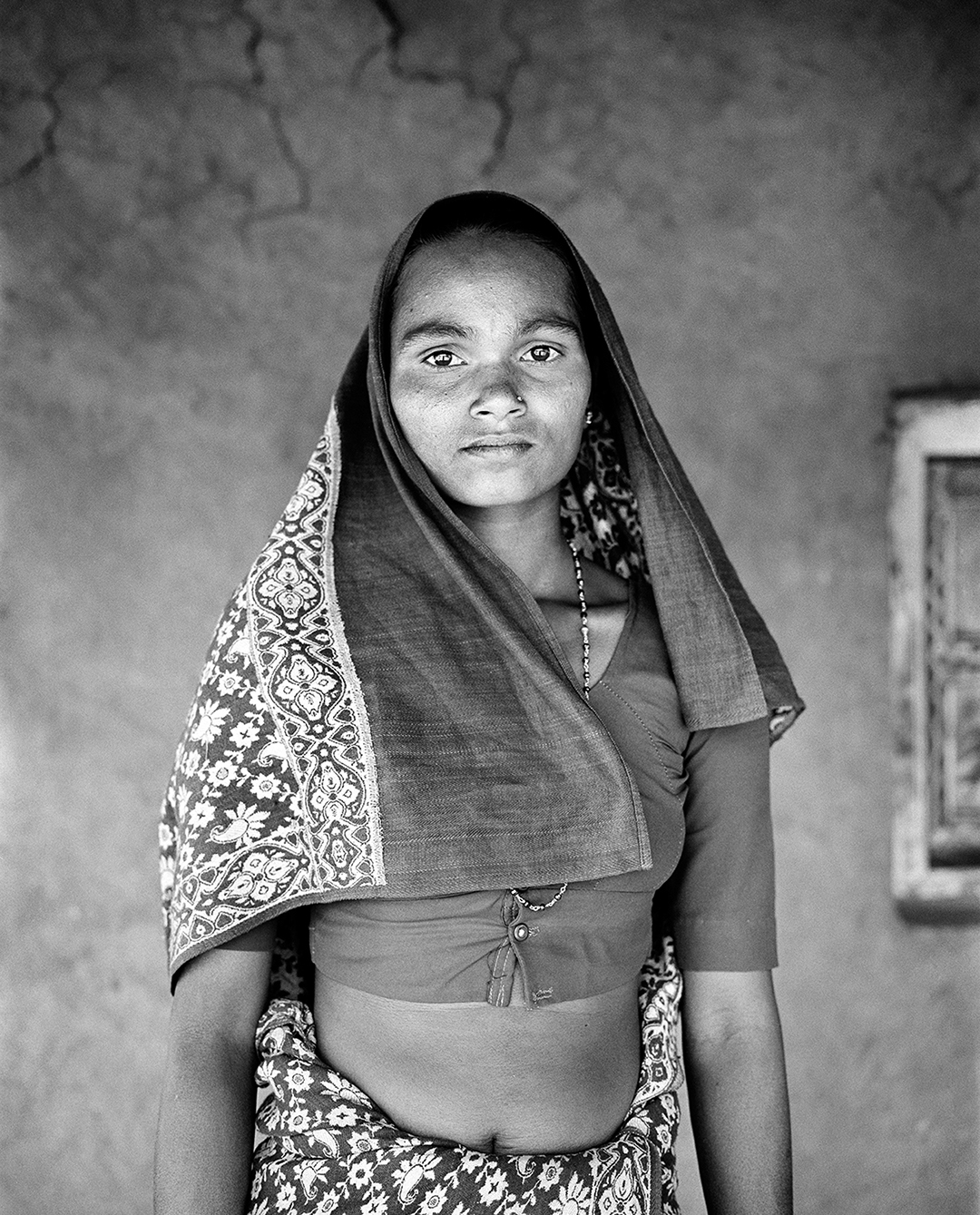

Robert Nickelsberg, the well known American photographer, in his ‘50 Years After Independence, 1997’, shows an India stuck in time. The photographs show some places untouched by modernity. His portraits tell the stories of villagers who are stuck in the past and seen through the eyes of a foreigner from modernity. Shot using media format Mamia camera– the images are sharp as if it has reached a space of perfection. It lingers, probing whether the viewers too have gotten stuck in a sort of time-lapse – reliving as history repeats itself. That way, the photographer’s choice to use portraiture to narrate this particular tale is both interesting and reverberating.

Mukul Roy’s ‘Women of India’ series is highly anthropological and sociologically relevant. Hearing about Mukul, former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi gave her an invite to photograph her. She has done both political and historical photo documentation, including the aftermath of the Bhopal gas tragedy. Photography was a kind of activism for her. Amid the vast Indian landscape, one can see the life of women here; some representing the innocence of a bygone era that also carried a lot of darkness. While watching her photos, several questions pierced me. What are my prejudices? What is the progression of a civilization? In this current period why our species is still the same as our ancient ancestors? It was as if nothing changed. Time, expansion of empires, cultures, art… all stuck in the sandy expense of time.

Nick Oza, an Indian American photographer, in his ‘Invisible Lines’ series, shows us the social confusions and the reality of being an immigrant. The subject is his own views on international immigration, narrated here by the photographs he clicked in the Indian state of Assam. The poverty of Assam and the overflowing of immigrants from Bangladesh for a better life are captured in his photos. Have they finally received the life they dreamt of, or, life has become more complicated? The truth lies somewhere in-between. The photos in this series were part of the Pulitzer nomination in 2010.

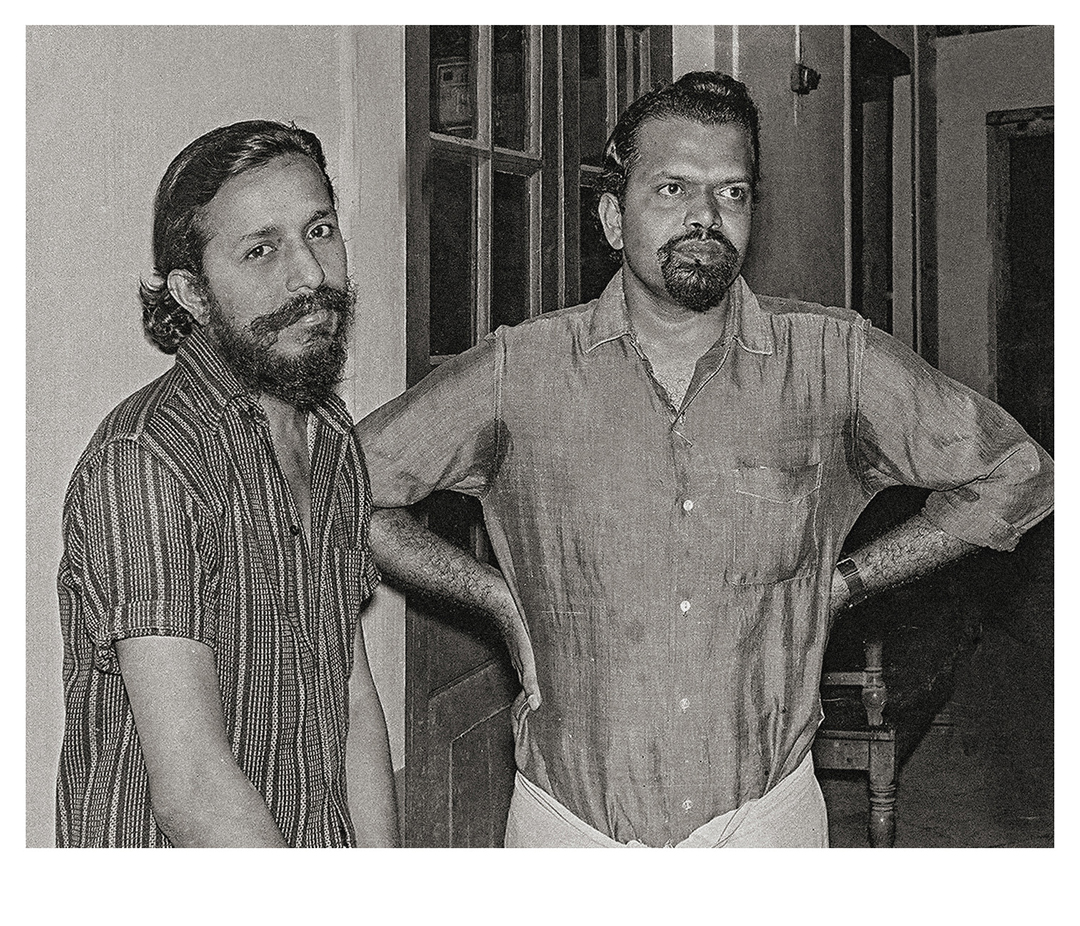

Punalur Rajan’s ‘Chronicles of Homeland’ tells the story of a land through portraits. Professional and intellectual in nature, he covers the personas of his homeland with all dexterity. His sad demise in 2020 is a great loss to the photography community. The range and persons he dealt with are the attractions of his works. As my home-town photographer, I feel a sense of pride, belongingness and nostalgia. He has given a visual image to the icons that each Malayalee has so admired.

Canadian Indian photographer Sunil Gupta, in his Mr. Malhotra’s Party, shows portraits of individuals representing the sexual minorities. The queer perspective is revealed in the Indian scene. In an interactive session, I could hear him talk about the hurdles he faced to practice both his art and sexuality in India. Although Sunil has also created other body of works in which intimate scenes were expressed, in this portrait series, there is a certain depth that encourages one to probe further – is there at all anything abnormal about people with different sexual interests? Aren’t grey areas of sexual preferences normal and have existed culturally and sociologically? From where and how did oppression erode the plausible space of cultural acceptance?

British photographer David Bate, in his ‘Machinic Unconscious’, is so right about this dystopian machine world. Machines are evolving, paralleling the science fiction movies and books. In his series, Bate uses the Freudian term unconscious which beautifully explains his work. The complex structures making the machine or a laptop is displayed in a more intellectual and understanding way. The unconscious mind or strata of the machine is a metaphor to display current scenes. This work is a child of current lockdown. Experimental in its own right, it is also satirical and visually engaging.

Xiangjie Peng’s ‘The Empire of Dwarves’ is something extraordinary. The photographs reveal strangeness and the photographer’s interest in subcultures. China is a place that is still not much known to the world audience. The political inhibitions have hindered a reading of this ancient country’s cultural essence. We have a long association with this country across the silk and spice routes; however, the current scenario has caused a lot of prohibitions. Peng beautifully shows the magical dwarf land in Yuan, China. I could feel parallels between the mysterious island of Lilliput and Peng’s work. Is it a real world that Peng has documented or is it an imagined reality? Re-imagined for the viewers, the works curiously urge one to travel back to those memorable days of childhood fantasy. It transported me to my memories of reading Gulliver’s travels.

Ram Rahman in his ‘Public and Private’ series takes us to largely political and sociological venues. An amalgamation of culture, protests, and the persons commanding political powers are the subjects. Ram interestingly blends the elite with the everyday. In his works, different worlds merge and become one continuum of the sociological signifiers.

Abul Kalam Azad in his Senti-Mental series talks about anthropology, psycho-social constructions, and other human-related subjects. Observing Abul Kalam Azad’s works, I could sense in him a hyper curious silent mind, always contemplating on roots and the mystical side of being a human. He is questioning the present and filling the past with his reflections. His exposure is huge and is one of my personal favorites. His works are regionally rooted, yet international in expression. In one word, his works are spellbound. His subjects are psychedelic and prints are multidimensional. His interest in south Indian history can be read between the lines. Man, civilizations, nature, aesthetics, and other subtle ideologies are evident in his works. Abul investigates his questions with his own tools and leaves the mark of those queries in his prints. He blends diverse subjects and techniques, transforms found images, questions the careless nature of ignoring our visual treasures, and further push the medium into the domain of experimental and conceptual – often leaving the viewer thoughtful. One can call him a visual poet.

Indian photographer Parthiv Shah in his ‘Jerusalem’ series speaks about an ancient race and land that are in chaos since the recorded history. Here, religion is shown with all its dexterity. The style is a kind of street photography with an artistic touch. The images linger – revealing a sort of serenity that is all too welcoming. It is an empowering parallel narrative.

Swarat Ghosh in his ‘Boxed’ series talks about modern work culture. Work is part of humans from the time of the formation of our society. The large web of global social systems is fueled by work. Our whole species is tied in this machine called work. The simple-looking photographs completely enlighten the cues of work culture. Shot before the lockdown period, interestingly, it is not only nostalgic memories of what was once considered normal but also an unraveling of closed perceptions that crowds work life. Indeed, his photographs reveal the workspace and the term called career which was frozen in lockdown. His angle and views make the usually ignored subjects and human arrangements interesting and engaging.

Indian photographer Alex Fernandes, in his ‘Goan Archetypes’ series, shows the social structure of Goa, rather sarcastically. Mario Miranda’s iconic cartoon characters become subjects for Alex. The roles were enacted by two theatre artists – playing all the different characters. It is a kind of Jugalbandhi that amalgamates the different art forms. In its concept, Goan Archetypes is exemplary. The art of studio portraiture reaches its beautiful pinnacle in Alex’s works. Each character becomes alive, often making one smile. The mind raves backs to identify our own experience with these archetype characters. Funny, engaging, well crafted, it borders in that thin line that connects the world of reality and imagination.

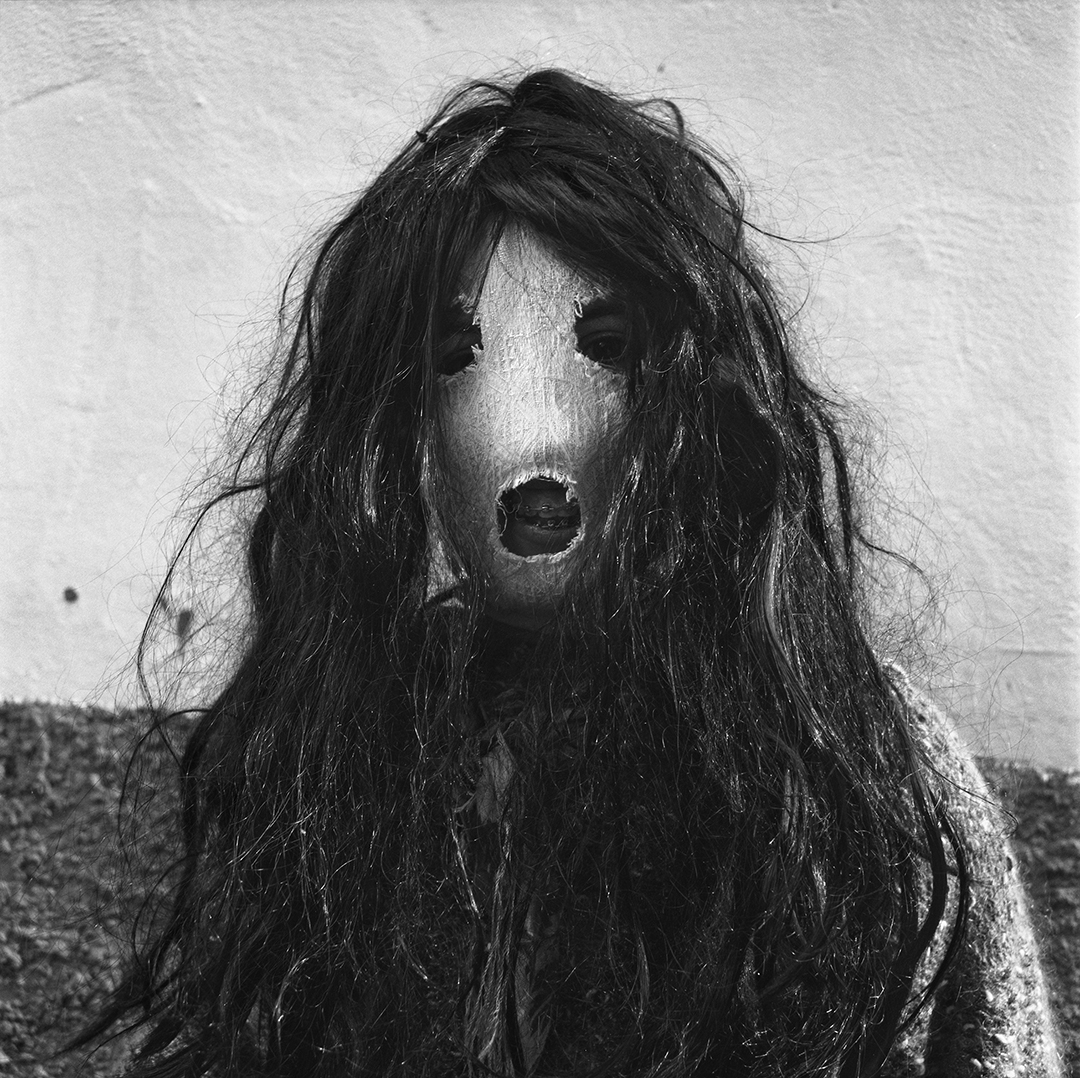

French photographer Yannick Cormier in his ‘Inauteriak’ series talks about the dichotomy of good and evil. Deviation, weird, grotesque, insanity, satanic, all these terms flashed before me while watching his work. From the most ancient days onwards humans are taught to be terrorized by the devil. Almost all religious texts warn people about the devil. The obsessive presence of the devil almost reaches that space of absurdity and nonsense. And, in absence, it is also of the presence of gods, of all things good. Yannick has done an extensive body of work and the consistency in his style is becoming a visual signature that he leaves in his meticulous works.

Indian photographer T Narayan’s ‘Behrupiya’, shows an art form popular in India, Nepal, and Bangladesh. The ritualistic performance is indeed a common experience – we have many variations of similar practices in South India as well. Yet, in magnetic colors, the works once again affirm how truly magical India is.

That way, there is a connection between the works of Yannick and Behrupriya. Yannick has been working on documenting these sorts of fancy-dressed ritualistic performances over a long period. There is a visible difference when one artist engages a long time with a particular concept. When an event becomes just one of the long list of photo opportunities, how much over powerful the images could be, it has conceptual gaps and intricate misspellings.

In a continuing context, Indian photographer Dinesh Khanna’s ‘Bhagoriya’ session presents a tribal festival of Madhya Pradesh. One can see his passion for colours in these pictures. What is India without its fabulous colors? In my musing, I categorize his works anthropologically. The family system, puberty, celebration of life, and folklore are manifested. In my opinion, he is one of the photographers who hold the legacy of modern photography. To create this body of work, Dinesh Khanna used an existing make-shift studio set up by another photographer. Going back in time, we are in fact moving forward.

Indian photographer RR Srinivasan, in his ‘MasiMaham: The Moon Festival of Five Elements’ series, talks about the festival of a primitive tribe of India called Irulars, on the seashore of Tamil Nadu. Moon and humans have a lot of stories together. The aim of the festival is to please the deity. India has a lot of festivals where people gather from generation to generation to continue practices. We just imitate cultures or whatever is handed over to us by our predecessors. Is it just repetition without a reflection, even though these gatherings are beautiful. A sense of belongingness and good feelings of oneness might be felt by the participants while the shaman performs rituals. We have this system from tribal days, but in modern times they can be seen in the form of rave parties in the beaches. Only the ways have changed but the activity is the same. Carefully crafted in all its essence, only man’s deities and legends have varied. But RR Srinivasan is not touching the peripheral aspects of festivals. His is a loud call for returning to the roots and a powerful reminder of the lands robbed and rights grabbed from the indigenous communities. The culturally rooted works speak of the unspoken issues that trouble the people of this land and challenge their core identity. RR is basically an activist and a film-maker, who has been actively involved in the Dalit and tribal movement in Tamil Nadu. This is what reflects in these seemingly straightforward images.

Emerging Indian photographer Taha Ahmad’s ‘A Displaced Hope’ talks about a genie worshipping community. Diversity of faith in a religious community is shown. His childhood memories along with his present curiosity have become subjects. Taha’s works stand apart, basically because it is fundamentally autobiographical. His concepts are usually close to home and when a question is asked from that space of familiarity, it is bound to hit the hearts.

Closely looking at these photographers’ works, though their context and expressions are varied, a few continuing threads can be identified – faith, religion, history, culture, tradition, identity –the very fabric that weaves our society. Photography is indeed the greatest modern invention that with its eternal quality leaves footprints for the future.

Shibu Arakkal, an Indian photographer, shows through his ‘Constructing Life’ series beautiful portraits of a community that builds homes and civilizations. Is it melancholia and detachment in the eyes of his subjects? Why are they broken, as if they are being reconstructed? Is it an expression of construction or the struggles of human existence? It is both philosophical and sociological in one breath.

Chandan Gomes, another Indian photographer, through his ‘Another Life, Another Time, Another Death’ series shows strangeness and bizarreness. His technically proficient works sometimes highlight violence. One would question why conflicts come to us. Individual and social disharmony and chaos could be the reasons. I am still pondering.

Lebanese American Rania Matar in her ‘On the Other Side of the Window’, connects the current lockdown and aesthetics. Confinement is a subject, and humans are always bound. Freedom is only a bridge to another cage. Emotions and strangeness are largely perceived; mood swings in isolation could be a better explanation for this. It is unlike what we experienced in the Indian context – probably the uneasiness of confinement and its mental repercussions were felt amongst our elite populations. But, it is more of the struggle for survival here. Probably that’s why it feels quite sentimental and alien.

India based French photographer Fabien Charuau in the ‘Rajpur’ series speaks about village life. It is like a visual diary of a traveler, filled with interesting anecdotes. And what makes it interesting is his unique viewpoint – they are random pictures, but they do weave a certain narrative that is both minimal and spectacular. One can engage with the subtle conversations in these images as the artist absorbs the Indian village scenario.

Ramu Aravindan, through ‘Ramu’s Encounter’, shows the photographs that were clicked during his wanderings. The humans, land, water bodies, garbage, and existence that appear in his photos can be grasped as his inner cues. There is a singularity in their continuity. His landscapes are poetic. Yet, they don’t miss the frails of human existence. This Kerala born photographer works in a rather unusual way – he spends hours speculating before creating his images. It is the silence within the silence that he searches and expresses. The stillness of photographs can provoke stillness as well as restless seeking. Why not – the artist asks? Isn’t stillness a summation of all movements?

Debamalya Ray Chaudry’s ‘Fragments of a Dying Man’ talks about a deviant and erotic life. The repression process is manifested in many places. Indeed, there is solitude in which one could sense more emotions than thoughts. Deb is powerful in his visual language – a treasure in fact. His personal turmoil becomes that of the society’s – for there is no line that divides an individual from the society that makes or breaks him/her. His is a work that requires further reading and deliberation – the artist in him is provocative. The human in him is not afraid of his own strengths and weakness. The emotions surge, but when expressed through photographs they become a rendering, a lover’s note filled with a secret language.

IQRA means to read or knowledge. Shot after the Delhi riots 2019, Indian photographer Vinit Gupta’s strength lies in narrating a story without being explicit. As Indian art historian Johny ML said during his felicitation of Images of Encounter show, a photograph reveals what happens before a photograph is taken. But what happens afterward is usually not revealed. And, there are certain photographs that demand action – and that way, what was done after seeing a certain photograph defines a society. IQRA is one such work that alarmingly wakes one up to what has happened, but at the same time demands a discussion regarding what steps are taken or should be taken. While Chandan Gomes works are visibly violent and touch about brutal realities, Vinit Gupta is nudging an inner response in a rather subtle way. Tragic and violent photos need not make one cringe but still can provoke.

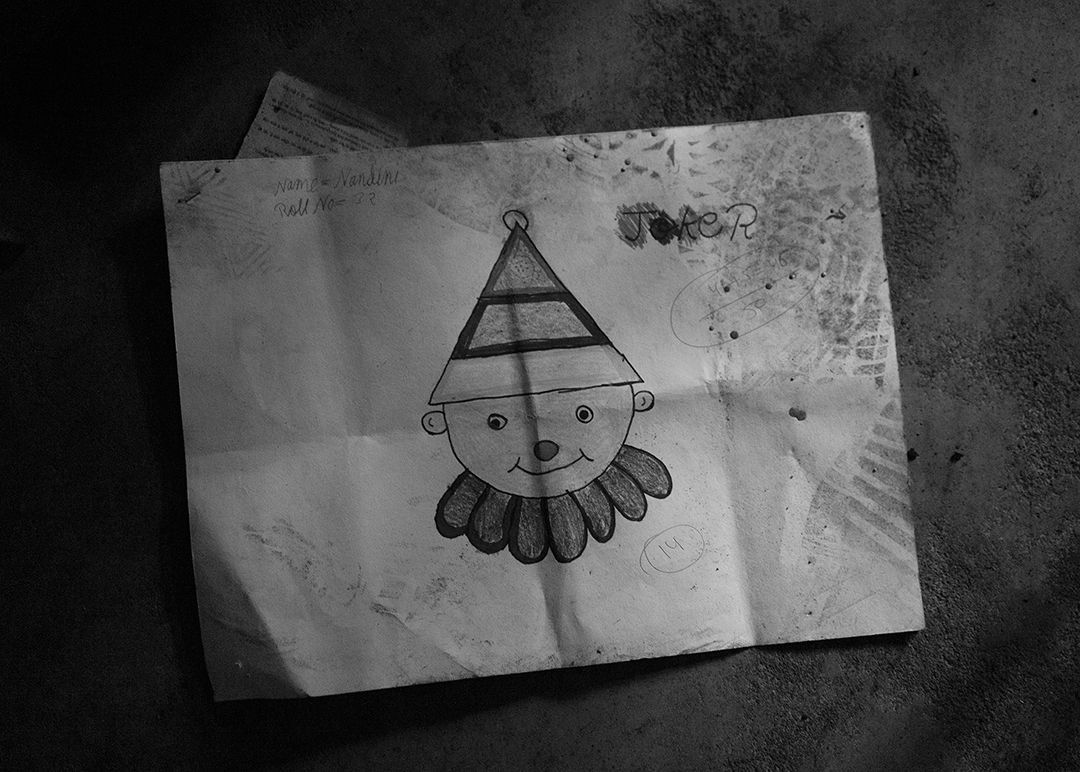

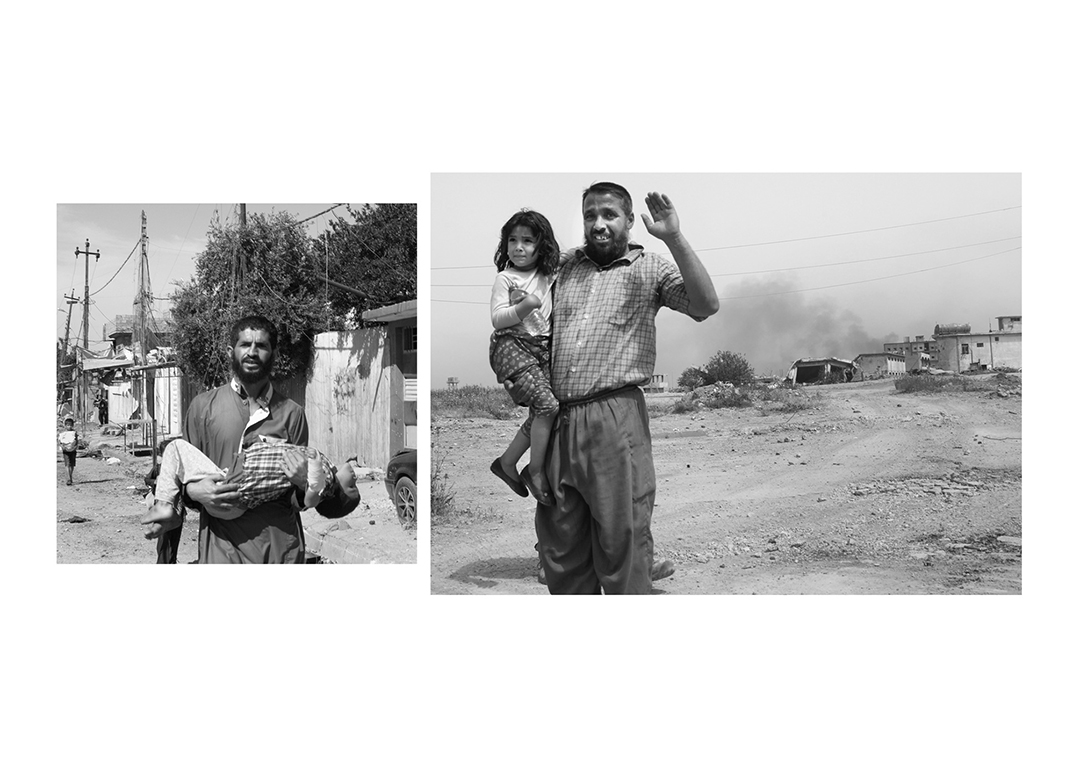

In continuation, Lina Issa, a Syrian photographer, presents Bruises of Exodus which is impressive in similar lines. Here too the violence and tragedy are palpable in every frame, yet its subtle expression makes one feel empathetic, rather than poking sympathy. The tremors of an exodus that shook West Asia can be felt through her pictures. War is always a curse on humans, her images tell us. One can see the dangerous life she might have lived to capture the political and deep social instability that wreaked havoc in the Iraqi city of Mosul. Migration is always is uprooting and life-shattering. It reminds many instances that happened close home – be it post-partition exodus or the recent walk by thousands of migrant works post the lockdown. Whether it is because of an epidemic or a conflict, any form of the forced exodus is unacceptable and painful. Photographs are powerful reminders of how society and its underpinning politics continue to oppress its very people.

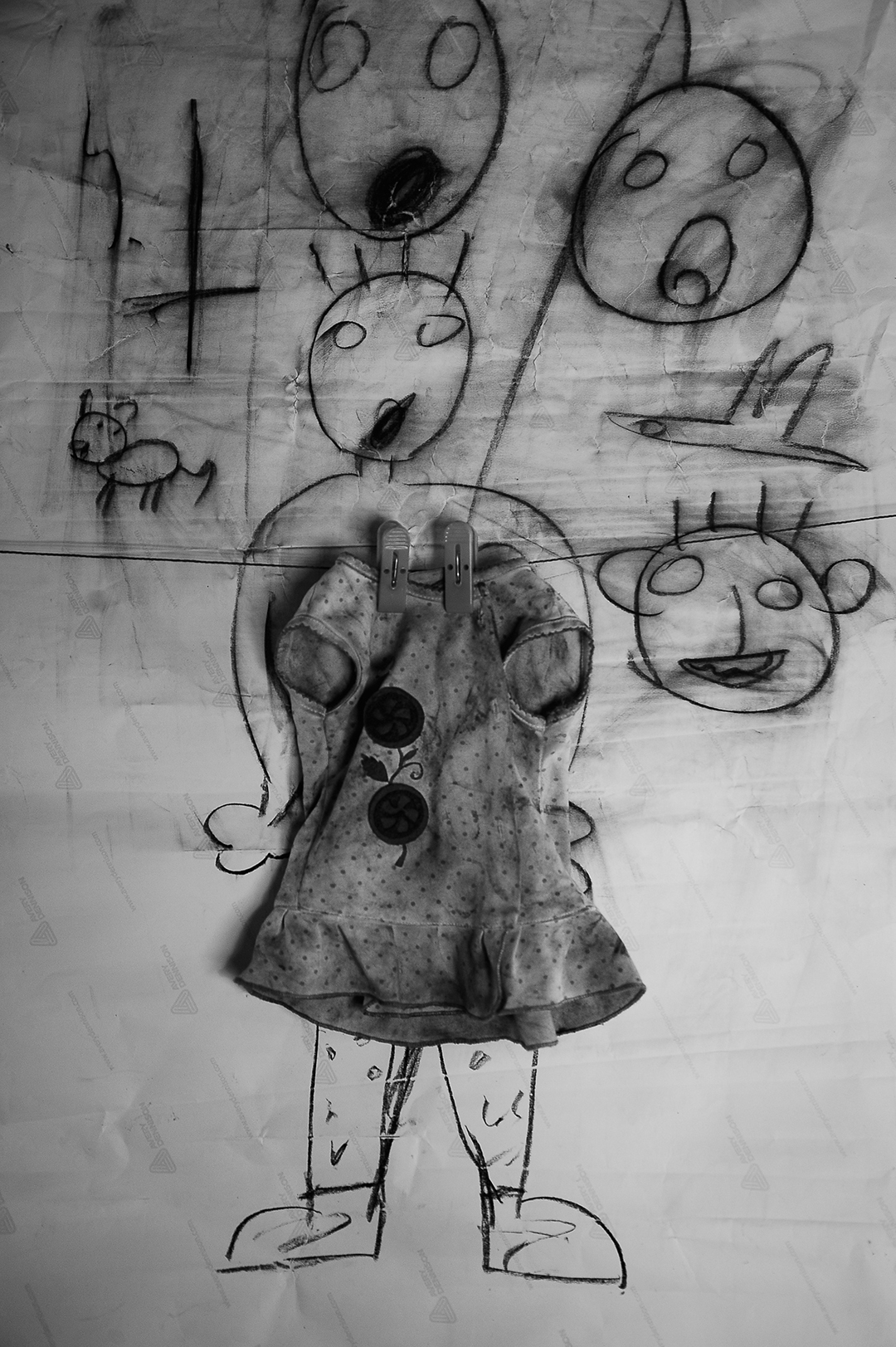

Arun Inham uses photography as a medium to further his interests in painting and sculpting. ‘A Canvas of Motions’ shows a kind of amalgamation of paintings and sculptures. His presentations, sometimes looking bizarre, have a subtle language. One can observe schizophrenic drawings in his substratum. Arun’s works are interesting also because there is a complete manipulation of settings. There is an influence of some popular international photographers in his works. As a budding photographer, Arun will have to study much further before developing his own visual language.

Naveen Gautham in his ‘Poochoodal’ brings to light the habit of women wearing flowers. His obsession with flowers and observations of women wearing the flowers lead to this documentation. Indians, especially South Indians, adore flowers. Flowers are part of various cultures and ritualistic worship across the country. It is beautiful documentation yet it lacks cultural clarity in its concept and expression. As an emerging photographer, Naveen has plenty of opportunities to further sharpen and make his mark.

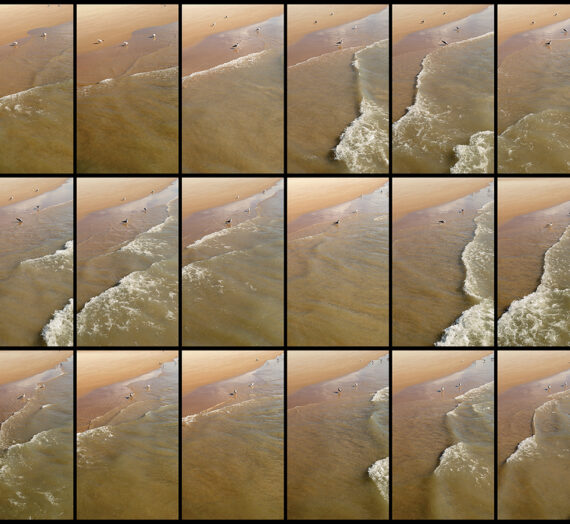

Ramith stands out in the exhibition as he has chosen to present moving images instead of still images. The curatorial team’s decision to include this as part of the Images of Encounter photography exhibition raises eyebrows. Probably, Ramith’s’Endless Horizons’, carries a certain stillness that is the fundamental quality of photography. The beauty of photography is because it is both independent and inter-dependent. When movements sculpted in time becomes one continuing moment, it becomes a poetic motion. Ramith, a young art student has luster for moving images.

Concluding my observations about the Images of Encounter, I would say this was a complete show of bravery from confinement. Limitations, if any, becomes ignorable, simply because of the novelty of the exhibition. When the whole world is stuck at home, art is finding new ways of expression. In visual art, photographs have their own place. It is not an ancient practice, but a modern memory, or recitation, poetry, history, man and his saga. It is more about what is it to be alive, what is this world, and what is observed. It involves the thought processes, perception, emotions, knowledge, beauty, sexuality, gods, deities, shamans, flowers, religion, sadness, euphoria, and nirvana, deliverance, discrimination, reasoning, outcast, rebellion, survival, adaptation, civilizations, time, lifestyle, impermanence, peace, chaos, repetition, gender, symbols, language, and also the ever-present void.

Published in 2021

Rahul Menon

www.imagesofencounter.com

Leave a Reply